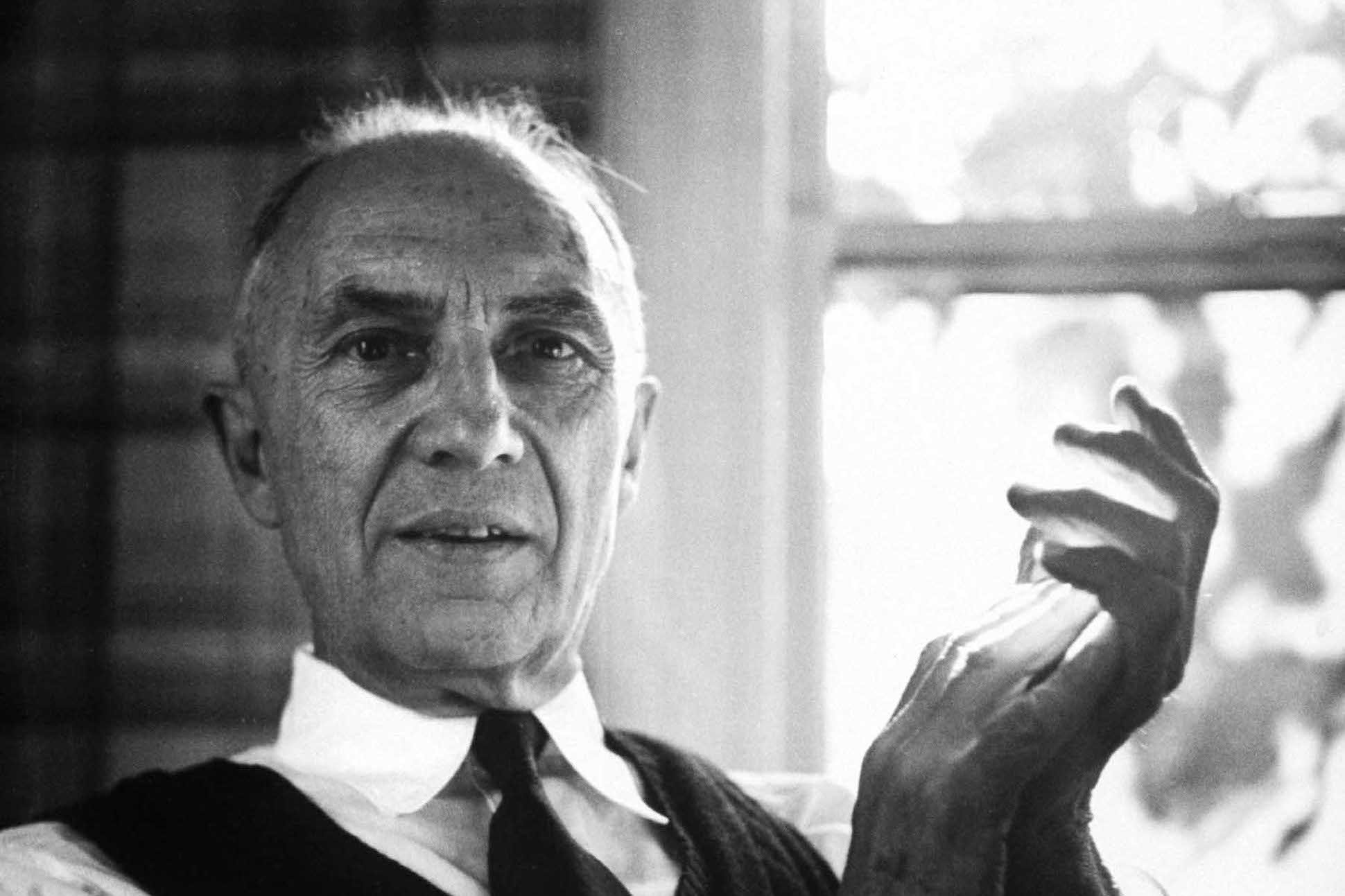

William Carlos Williams

Words by Orlando Callegari Jr.

William Carlos Williams, photo by Lisa Larsen/The LIFE Picture Collection.

“Who knows the Palisades as I do

knows the river breaks east from them

above the city—but they continue south

—under the sky—to bear a crest of

little peering houses that brighten

with dawn behind the moody

water-loving giants of Manhattan.”

(January Morning: Suite, lines 58-64)

Chances are, William Carlos Williams scribbled those stanzas on the back of a prescription blank or recited them to his secretary between house calls while walking the same streets we travel today. The stethoscope poet lived like so many of us do here: with a nose to the grindstone while simultaneously chasing the beauty of life.

Williams’ journey began when he discovered his artistic soul writing poetry in high school. His upbringing was never short on Art (his mother was a lover of theater and painting while his father introduced his sons to classic literature) however, according to biographer, James Bresslin, Williams’ parents instilled in him “rigid idealism and moral perfectionism” which led Williams to a practical career in medicine. After getting his doctorate at the University of Pennsylvania and interning in New York, Williams re-settled in his hometown of Rutherford in 1910.

William Carlos Williams as intern at Nursery and Child's Hospital.

Williams worked as a country doctor, making house calls and delivering children, while squeezing in moments of reflection and imagination during his travels. With sons to put through college, he adopted the can-do attitude of a factory worker rather than the carefree life of a village bohemian.

During these years, Williams lead a literary movement with most of his patients never recognizing his other life. He wrote 600 poems, 52 short stories, four full-length plays, four novels, a biography, an autobiography and the epic poem, “Paterson”, while spearheading the Imagist movement (characterized by concise language and precise imagery).

Rather than limit his creativity, Williams said his medical work brought him inspiration, allowing him to "follow the poor defeated body into those gulfs and grottos ... , to be present at deaths and births, at the tormented battles between daughter and diabolic mother."

Eventually, his seemingly conformist lifestyle put him at odds with his contemporaries. While Williams remained firmly bourgeois, poets and friends such as Ezra Pound and TS Eliot embraced European culture. This drove a wedge between Williams and much of the literary world.

Health problems added to Williams’ woes later in life. He had a series of strokes and heart attacks through the late 1940s. In 1949, the Library of Congress invited him to be a consultant; an invitation he had to decline due to his health. However, he reconsidered in 1952. Unfortunately, accusations of communism were common during these years and Williams became another casualty. The Library of Congress eventually rescinded the offer.

Despite these troubles, Williams’ benefited from renewed admiration from the next wave of literary greats who took queues from his unique approach to poetry. Writers such as Allen Ginsburg and other Beat poets revered Williams due to his accessible language and style. Pulitzer Prize-winning poet, Robert Lowell, once said, “Paterson is our Leaves of Grass" comparing Williams’ magnum opus to the work of Walt Whitman.

Williams was to receive his greatest honor in 1963: the Pulitzer Prize. Unfortunately, he passed away in his sleep on March 4th of that year, before he could accept.

William Carlos Williams, photo taken from New Directions Books.

“Work hard all your young days

and they'll find you too, some morning

staring up under

your chiffonier at its warped

bass-wood bottom and your soul—

out!

—among the little sparrows

behind the shutter.” (Lines 72-79)

At the ceremony renaming the Rivoli Theater “The Williams Center”, Williams’ sons described him as down to earth unlike his artist friends.

“His energy was inexhaustible,” said William E. Williams. Paul Williams said, “I’m honored that my father is being used as a symbol of a rebirth, a rejuvenation for Rutherford.”

William Carlos Williams (1883-1963) – photo courtesy the William Carlos Williams Papers, Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Beinecke Library, Yale.

“All this—

was for you, old woman.

I wanted to write a poem

that you would understand.

For what good is it to me

if you can't understand it?

But you got to try hard—

But—

Well, you know how

the young girls run giggling

on Park Avenue after dark

when they ought to be home in bed?

Well,

that's the way it is with me somehow.” (Lines 82-95)

Photo taken from The William Carlos Williams Society website.

“The William Carlos Williams Society encourages and advances the study of Williams’ writing and its relationships to modern poetry and other literary forms, both in North America and in other areas of the world.”

Tickets for all events can be found at williamscenter.co/events.